The Rise of Residential Real Estate

Aug 29, 2012

When Nick Athanail strolls around the Flatiron district, he often finds himself humbled by the community’s residential architecture. “It’s one of my favorite features,” notes the Senior Vice President/Associate Broker at The Corcoran Group, where he specializes in the area’s residential sales and also serves as a Board member of the Flatiron/23rd Street Partnership and Vice Chair of Manhattan Community Board 5. “Some of the area’s most beautiful buildings are also magnificent landmarks. It adds distinctiveness to the neighborhood not found anywhere else.”

Within in the last decade, “nearly two million square feet of residential space has been created or converted to residential use in the Flatiron district, with one million more planned,” according toFlatiron: Where Then Meets Now, the 2012 report published by the Flatiron/23rd Street Partnership. Thousands of new apartments have resulted in the rapid rise of new residents and transformed the community from primarily a commercial to a mixed-use one.

“The last 10 years saw an incredible boom in residential development,” says Athanail. “Practically every vacant space, parking lot, or underdeveloped parcel was restored or rebuilt to its maximum residential capacity.” And, he adds, “It’s one of the fastest growing residential neighborhoods in the city. Flatiron has everything: a central location, easy access to transportation, world-class homes, shopping and dining, an exciting nightlife, and a jewel of a park, all surrounded by historical beauty. People just want to live here!”

Active or planned residential developments include a 20-story condo at 241 Fifth Avenue, rental and condo occupancy at the 42-story 400 Park Avenue South and 145 condo units at 1107 Broadway, which was once part of the famed International Toy Center. “This building is now back on track to become a luxury condo with a $100 million renovation planned for both the interior and exterior,” cites Athanail. “The location of these exceptional properties will create incredible demand for the residences there and pricing for these homes is expected to be at a premium to even Manhattan’s most prestigious neighborhoods.”

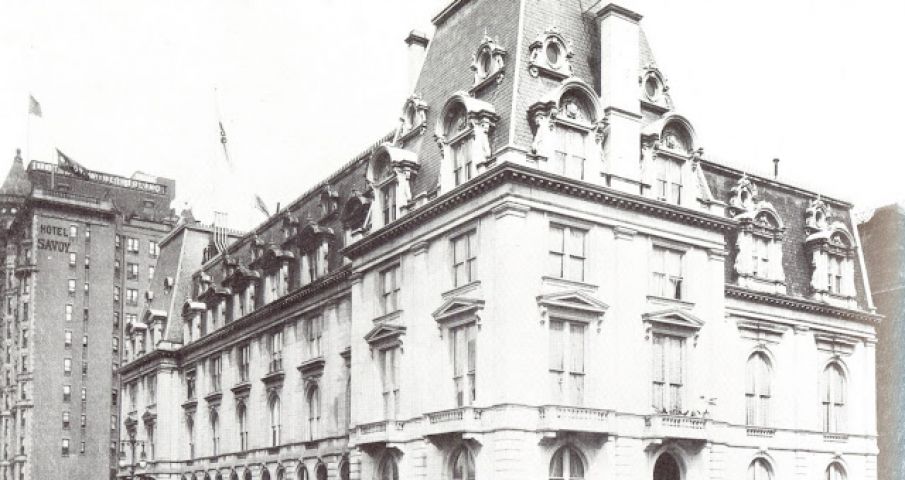

The historic launch of luxury residential living in Flatiron can be traced back to the late 1800’s with the Stevens House, one of the earliest and best known apartment buildings in the district. Initially, it was built for Paran Stevens, who was then one of the country’s most successful hotel proprietors. In 1870, Stevens commissioned architect Richard Morris Hunt to build the property that would occupy the southwest corner of 27th Street between Fifth Avenue and Broadway. A close friend of the family, Hunt was also celebrated by colleagues as the “dean of American architecture,” and best known as the chief concept designer of the base and pedestal for Frédéric-Auguste Bartholdi’s Statue of Liberty.

The blueprint for the Stevens House was derived from the period’s popular Parisian-style flats. It was envisioned to be an “eight-story brick building with a Nova Scotia freestone front, a mansarded slate roof, shops on the ground floor and apartments for 18 families,” according to Alone Together: A History of New York’s Early Apartments by Elizabeth Collins Cromley. Construction of the building was completed in 1872.

However, in that same year, the death of Stevens at age 69 and the economic panic of 1873 forced a remodeling of the luxury residence to a conversion that would later be known as the Victoria Hotel in 1879, and reportedly accommodate 500 guests. It appeared to some that the Stevens House “proved a prototypical, if ill-fated, experiment in the establishment of the luxury apartment house,” according to Rise of the New York Skyscraper: 1865-1913 by Sarah Bradford Landau and Carl W. Condit.

But for others, the property was viewed as a forefront into the future of urban apartment living. “The extraordinary height, steam heating, steam elevator, forced mechanical ventilation, gas ranges, and various other modern contrivances of daily life, made Stevens a technological landmark,” stated author Richard Plunz in A History of Housing in New York City: Dwelling Type and Social Change in the American Metropolis.

“Apartment hotels such as the Stevens’ House offered the domestic features of an apartment house, eliminating, if one wished, the kitchen in favor of a communal kitchen that would prepare meals, made to order, or provide cuisine from the house restaurant,” wrote Miriam Berman in her book Madison Square: The Park and Its Celebrated Landmarks. “It replaced the concierge with a manager and offered the luxuries of a hotel without the stigma of risqué living. Prospective tenants were lured by the provision of many modern amenities, including artificial refrigeration and long-distance telephones. These were commercial conveniences not available in private dwellings at this time.”

And now, more than a century later since the reinvention of the Stevens House, the resurgence of residential units in the area continues continues in this vibrant and exciting community. “I love the Flatiron district for its existing diversity,” declares Athanail, who also calls the district his home. “Being here, for me, always feels like I’m in the center of ‘where it’s at.’ My friends always tease me because I hate to leave Flatiron. Whenever they want to go somewhere else to shop, or dine, or party, or relax, I always know a better place right here!”

Image via The Gilded Age Era Blog