Role of 1930s New Deal Programs in Flatiron

Sep 8, 2020

When President Franklin Delano Roosevelt spoke the memorable words “the only thing we have to fear is fear itself” during his first inaugural address on March 4, 1933, he set out to inspire Americans to engage in work-related programs to ignite the economy out of Great Depression. This month, the Flatiron Partnership highlights some of the notable policies known as New Deal programs that were instituted by Roosevelt and Congress to offer relief, recovery, and reform to the Flatiron District and other communities across the nation.

With the Relief Appropriation Act of 1935, “the Works Progress Administration (WPA) was established with approximately $5 billion in funding, providing public jobs for the unemployed–the largest jobs initiative in American history,” notes The Encyclopedia of New York City. This Executive Order-created agency was later renamed as the Works Projects Administration in 1939.

Other relief programs included the Public Works Administration (PWA), initiated in 1933, which “paid private contractors to build large-scale projects proposed by states,” the National Youth Administration (NYA) that began in 1935 as an agency that hired young men and women who were either in or out of school, and the Federal Emergency Relief Administration of 1933 (FERA), which awarded “grants to states for works programs to hire the unemployed and provide direct relief payments to the indigent.”

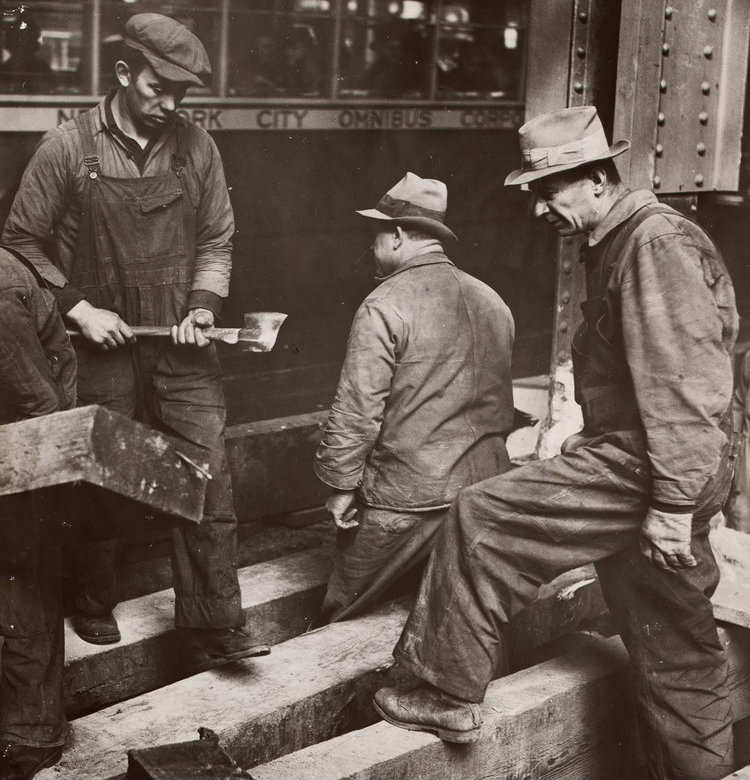

Subway excavation workers by Andrew via NYC Department of Records and Information Services.

The railways were a major form of mass transit for New Yorkers and the system was a work in progress. To help subsidize and set in motion the public system’s future for generations to come, PWA funds were issued for the line’s construction. The proposed Independent Sixth Avenue subway line (IND) was viewed as the modern-day answer to the former elevated railway system. This new underground corridor, which featured six IND stations, including the 23rd Street subway stop in Flatiron, could transport a rider for a nickel under Sixth Avenue.

For a reported cost of nearly $60 million, the two-mile portion of the IND line made its debut on December 15, 1940. “Mayor Fiorello La Guardia had dedicated it to public use by cutting a red, white and blue ribbon stretched across a battery of turnstiles at the south end of the huge station at Thirty-Fourth Street,” noted The New York Times that day. Most importantly, the subway structure generated jobs for “657 additional operating employees, trainmen and station agents …131 maintainers, trackmen, and special policemen,” wrote The Times.

Admiral Farragut Monument at the north end of Madison Square Park via NYC Parks.

The mid-1930s also introduced the WPA-sponsored restoration efforts of national monuments. One Flatiron statue in need of repair was Madison Square Park’s Rear Admiral David Glasgow Farragut. Located at the north end of the Park at 25th Street, between Fifth and Madison Avenues, the 9-foot tall Farragut statue was granted a Park dedication in 1881 to honor the Rear Admiral’s defeat of Confederate forces at Alabama’s Battle of Mobile Bay in 1864, where he reportedly proclaimed his immortal phrase: “Damn the torpedoes…full speed…ahead!” Several decades later, New Yorkers would pull together to restore the Farragut statue. With the readiness of the team underway, according to The New York Times on August 23, 1936, “expert carvers… will soon be at work on a pedestal for the famous Farragut statue”.

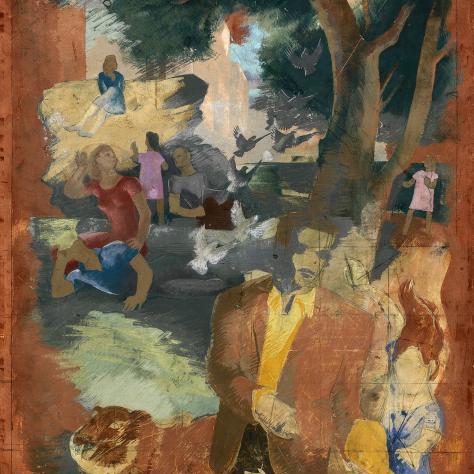

Robust funding of the arts was also a signature of the New Deal. Harry Hopkins, who led New York City’s WPA, declared in response to criticism of federal support for the arts, “[artists] have got to eat just like other people.” The Treasury Department chose to commission eight murals by architect Kindred McLeary to appear inside the Madison Square Post Office, located at 149-153 East 23rd Street, between Lexington and Third Avenues. This facility was reportedly the “most important postal station in New York City.” McLeary’s creative artistry featured City scenes ranging from Central Park to Wall Street to Greenwich Village.

Scenes of New York-Central Park by Kindred McLeary via Smithsonian American Art Museum.

Another local art commission included nearly 1,000 square feet of oil on canvas murals by artist and painter Erle (Earl) Lonsbury displayed at the 69th Regiment’s Lexington Avenue Armory headquarters, located between 25th and 26th Streets. Lonsbury’s Armory wall murals featured the Regiment’s most noteworthy missions he Wheatfield at Gettysburg in 1863, the 1918 Battle of the Ourcq, and a New York welcome home parade from 1865.

WPA and municipal funds were also used to pave the way for a street redesign that included the Fourth Avenue expansion, now known as Park Avenue South, between 14th and 23rd Streets. Reportedly, 2,500 WPA men removed 33 miles of trolley tracks throughout New York City.

The end result of New Deal programs and related infrastructure proved to be a success. By the mid-1940s, many programs ended operations due to various factors, including worker shortages created by World War II. President Roosevelt, a cousin of Flatiron native and former U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt, expressed great satisfaction with the achievements and accomplishments the policies provided to the populace and the architectural upgrades that reshaped structural designs.

During his third inaugural address on January 20, 1941, President Roosevelt declared that “most vital to our present and to our future is this experience of a democracy which successfully survived crisis at home; put away many evil things; built new structures on enduring lines; and, through it all, maintained the fact of its democracy.”

Photo Credit: NYC Department of Records and Information Services