Mohawk Ironworkers Give Rise to NYC Skyscrapers

Nov 19, 2021

November is Native American Heritage Month. In honor of contributions made by Mohawk, or Kanienʼkehá:ka, ironworkers who helped construct New York City’s iconic skyline, the Flatiron Partnership highlights the role of the group in the area’s building boom era of the 20th century.

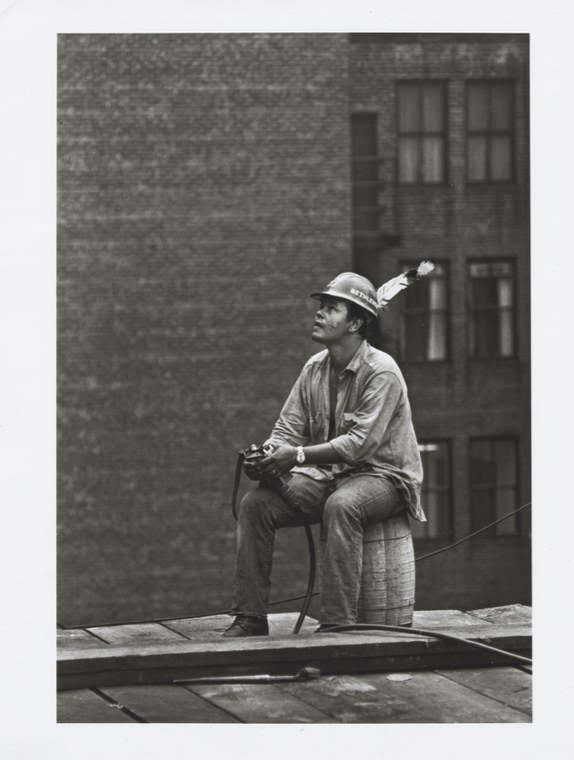

Photo Credit: David Grant Noble

Mohawks are members of the Haudenosaunee, commonly known as the Iroquois Confederacy, which also includes the Oneida, Onondaga, Cayuga, Seneca, and Tuscarora nations. During the turn of the 20th century, construction job opportunities began to flourish in North America, and soon Mohawks from Canada and upstate New York would seek employment as ironworkers. “New York was by far the largest city in the United States in 1900, and the richest,” wrote Jim Rasenberger in High Steel: The Daring Men Who Built the World’s Greatest Skyline. In a number of U.S. cities, explained Rasenberger, “skyscrapers had moved out of their infancy and into their rowdy adolescence, and New York was where they came to spend it.”

According to the website for the National Museum of the American Indian, “Haudenosaunee men began ‘walking iron’ in 1886, when they were hired to work on a bridge being built over the St. Lawrence River. Upon completion of the bridge, Haudenosaunee men began their tradition of ‘booming out.’” The term characterizes the urban migration by ironworkers who left their Native communities to find employment elsewhere. Reportedly, Mohawk ironworkers began working in regions as far south as New York City in 1901. “The men were thrilled to be working away from home and seeing new sights,” said Lynn Beauvais, a Kahnawake resident and grandmother from a fourth-generation ironworker family (via history.com). “They were a band of brothers.”

Walter Jay Goodleaf – Photo Credit: David Grant Noble

Mohawk ironworkers may have been members of construction crews who built the popular steel-framed properties during this period, including the Flatiron Building and Metropolitan Life Insurance Company’s Clock Tower. Located at the crossroad of 23rd Street, Broadway, and Fifth Avenue, the Flatiron Building was completed in 1902. The Clock Tower at Madison Avenue between 23rd and 24th Streets was finished in 1909. “Performing dangerous work several hundred, if not several thousand, feet up in the air requires amazing concentration, courage, and grit—the very qualities the Mohawks would ascribe to their ancestors throughout their long history,” wrote David Weitzman in Skywalkers: Mohawk Ironworkers Build the City.

Flatiron Building – Photo Credit: Skywalkers: Mohawk Ironworkers Build the City by David Weitzman

By the early 1920s, according to High Steel author Rasenberger, “Mohawks were regularly crossing the border to work on bridges and buildings up and down the Eastern Seaboard, traveling together in tight four-man gangs, communicating on the steel in Mohawk, boarding together wherever they could find inexpensive housing.” In 1925, however, a Mohawk ironworker was arrested for illegal immigration in Philadelphia. The case resulted in a landmark federal court decision in 1927. Citing the Jay Treaty, noted Rasenberger in High Steel, “the judge ruled that Mohawks, whose land had once overlapped parts of both countries, were entitled to pass freely over the border from Canada into the United States.” When they arrived in New York City, many Mohawk ironworkers and their families reportedly resided in Brooklyn’s North Gowanus section, now known as Boerum Hill, around Atlantic and Fourth Avenues.

Photo Credit: Mohawk Ironworkers from Kahnawake Locals 40 & 361

Some of the notable skyscrapers Mohawk ironworkers would help produce include the Empire State Building, completed between 1930 and 1931, the Chrysler Building in 1930, and the launched construction of the World Trade Center towers during the late 1960s. When the 9/11 terrorist attacks occurred, Mohawk ironworkers helped with the recovery, as well as the construction of the new One World Trade Center, or Freedom Tower, which opened in 2014. “For many Haudenosaunee communities, ironworking has become a tradition,” notes the National Museum of the American Indian’s website about the ironworkers who are also union members of the Kahnawake locals 40 and 361. “They learn from and with people they trust. Today they continue to work on high steel, carrying the Haudenosaunee reputation for skill, bravery, and pride into the twenty-first century.”

Header Photo Credit: David Grant Noble via National Museum of the American Indian.

Thumbnail Photo Credit: David Grant Noble via National Museum of the American Indian.