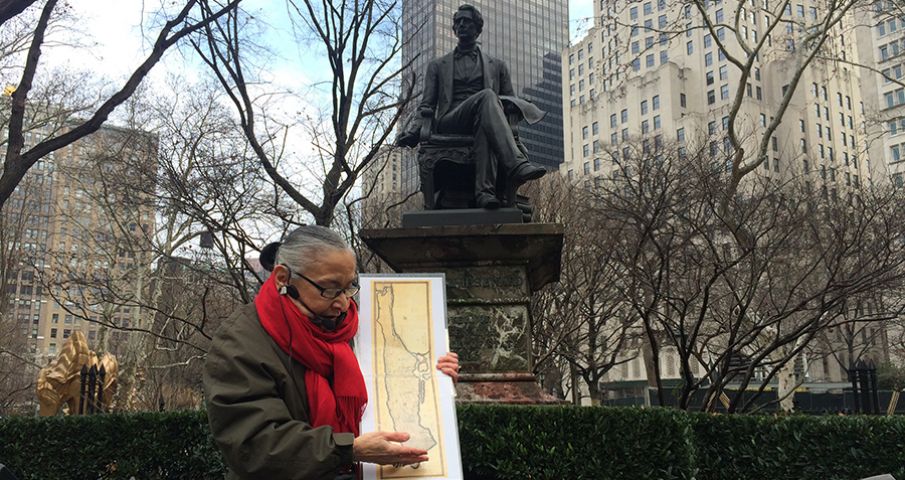

Miriam Berman

May 3, 2010

In her role as one of the Flatiron Partnership’s guides for the weekly walking tours and as the author of a highly acclaimed history of the neighborhood, Miriam Berman has solidly established creds as an urban archivist.

It is a calling that came to her in mid-career, almost 20 years after she launched Miriam Berman Graphic Design and began creating books, catalogs, brochures and other printed matter for clients ranging from the Metropolitan Museum of Art to the International Center of Photography.

Berman earned a BFA from Pratt Institute in 1965, but it wasn’t until the early 1980s, while working out of a penthouse office in the Flatiron Building, that she went to an exhibit of picture postcards at a midtown hotel and had the epiphany that led to a second career as an author, historian and collector of New York lore.

“I had moved into the Flatiron Building in 1978,” she said, “and although I suspected there was something special about it because of the wonderful sunset views from the penthouse — you could see the Statue of Liberty from there — to me it was basically just another office building.”

At the postcard show, however, Berman was dazzled by the hundreds of vintage cards that depicted the building, as well as many others that showed historic views of Madison Square.

“The Flatiron Building and the picture postcard seemed made for each other,” she said. “The shapes were just right.”

Indeed they were. The building was completed in 1902. The “golden age” of picture postcards in the U.S. started only five years later, when the government allowed a divided back for the address and a message, while the front remained completely clear for a picture.

“I saw buildings on those cards that seemed sort of familiar, but there was something a little ‘off’ about them,” Berman said. “I realized I was looking at the bones of the district, but slightly askew. For example, a picture of the Fifth Avenue Hotel reminded me of the Toy Building.”

The International Toy Center, as it was once formally known, or 200 Fifth Avenue, now stands where the hotel once stood, at 23rd Street.

Berman began collecting cards and stories, memorabilia and ephemera, eventually realizing she had the makings of a book. “Madison Square: The Park and Its Celebrated Landmarks” was published in 2001 and is now a collector’s item.

Berman kept an office in the Flatiron Building, which she now likens to “a piece of sculpture,” for 10 years, then set up shop in 210 Fifth Avenue, a lovely 1901 Belle Epoch building with balconies and bay windows. She remained there for 20 years and now operates her graphic design business out of her Greenwich Village apartment.

In the more than three decades she’s been studying the area, she’s seen numerous changes, from the rebirth of Madison Square Park to the return of residential accommodations. She sees that development as history coming full circle, harkening back to the days when the district was home to some of New York’s most illustrious families.

On May 26, she will discuss another aspect of Flatiron life — its legacy of fine dining — when she participates in “From Delmonico’s to Danny Meyer: Feasting in Flatiron Since the Gilded Age” a BID-sponsored public event.

“I would love to have dined at Delmonico’s,” she said. “It was so elegant, the beautiful service . . . the attention to detail.”

And what might she have ordered?

“Definitely the Baked Alaska,” Berman replied. “I’ve never had Baked Alaska. And the Lobster Newberg. I have eaten Lobster Newberg. It was good . . . but it wasn’t Delmonico’s.”