Legacy of the Great Blizzard of 1888 in Madison Square

Jan 7, 2021

As the neighborhood weathers this year’s winter season, the Flatiron Partnership looks at the legacy of the Great Blizzard of 1888 in the area then known as Madison Square.

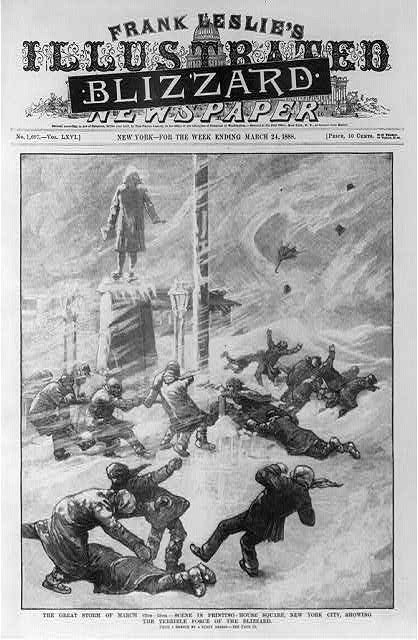

With temperatures in the mid-50s, it felt like an early spring day in New York City on March 10, 1888. But soon, an unexpected change in climate would alter the atmosphere. “Cold Arctic air from Canada collided with Gulf air from the south and temperatures plunged,” noted History. “Rain turned to snow and winds reached hurricane-strength levels. By midnight on March 11th, gusts were recorded at 85 miles per hour in New York City. Along with heavy snow, there was a complete whiteout in the city when the residents awoke the next morning.”

(Photo Credit: Library of Congress)

The Great Blizzard of 1888, also known as the Great White Hurricane, dropped as much as 55 inches of snow across the northeastern region of the United States from March 11th to 14th. “There were numerous accounts of people stranded and freezing to death,” writes the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. “The storm became legendary in New York City: as the economy was struggling, most workers went to their jobs regardless of the weather conditions. More than 400 people died from this storm, 200 in New York City alone.” Property damage in the five boroughs was estimated at $25 million.

For its nearly 2 million occupants, the city’s “many early risers on the 12th were dazed to find their doors and first-story windows covered by packed snow. Four-fifths of its 10,000 telephones were silent, and practically all of its electric lights and the great majority of its more numerous gas lamps were blacked out that night,” wrote Blake McKelvey in Snow in the Cities: A History of America’s Urban Response.

“When the storm struck, though, the technological conveniences and amenities of urban life were suddenly exposed as vulnerabilities,” reported The Atlantic on January 26, 2015. “Late 19th-century cities were monuments to man’s mastery of nature. Elevated railroads whisked passengers about; streetlights banished the darkness of night; telephone and telegraph wires crisscrossed the roads; horses hauled hundreds of millions of riders around the street railroads; and delivery carts ferried coal, dry goods, and all conceivable comestibles about the streets.”

(Image Credit: Library of Congress)

In Madison Square, elevated railways were delayed due to the storm. “Trains on Sixth Avenue were blocked much earlier on account of the curves, and the greater demand for transportation on that division,” wrote The Sun newspaper on March 13, 1888. “At 10 minutes past 10, a train stopped at 23rd Street, and after a wait of several minutes, the guards announced that there was a solid block of trains extending southward as far as Chambers Street. Most of the ‘standees’ and a few of the others promptly left the train, and proceeded the rest of the way downtown on foot. At that station, the ticket agent had sensibly closed the gate to his office, so that patrons were not induced to buy tickets and endure a hopeless wait upon the chilly platform.”

But not all Madison Square area businesses shuttered their doors. Some local residents and stranded visitors chose to see the Barnum & Bailey Greatest Show on Earth circus attraction at Madison Square Garden on 26th Street and Madison Avenue. According to venue proprietor P.T. Barnum in The New York Times on March 13, 1888, the “storm might be a great show, but he still had the greatest show on earth and he wants everybody to come to see for themselves.”

There was a three-hour matinee and also an evening show on March 12th. Each show entertained about 100 spectators and featured animals such as a “wonderful performing goat,” reported The New York Times on March 12, 1988. “If only one customer had come, I would have given the complete show,” said Barnum, according to American Heritage. “My duty is to the public and nothing shall ever keep me from honoring that duty, except Judgement Day itself.” Three years later, Barnum reportedly died of a stroke at the age of 80 on April 7, 1891. The website barnum-museum.org notes that some of the final words from the showman included the question: “What were the receipts at the Garden?”

For another neighborhood notable, the blizzard proved to be a perilous plight. Roscoe Conkling, a former U.S. Senator and House of Representatives member, was a $100,000-a-year lawyer on Wall Street. On March 12th, Conkling recalled that he was “not thinking that the city would be dark at night” when he left his downtown office, reported The Sun on March 14, 1888.

Conkling soon discovered that “there wasn’t a cab or carriage of any kind to be had. Once during the day, I had declined an offer to ride uptown in a carriage, because the man wanted $50, and I started up Broadway on my pins. It was dark, and it was useless to try to pick out a path, so I went magnificently along shouldering through drifts, and headed for the north.”

The athletically fit attorney, who engaged in the sport of boxing as a form of exercise, confessed that he “was pretty well exhausted when I got to Union Square. There was no light, and I plunged right through on as straight a line as I could determine upon. When I reached the New York Club at 25th Street I was covered all over with ice and packed snow, and they would scarcely believe me that I had walked from Wall Street. It took three hours to make the journey.” ‘

(Photo Credit: NYC Parks)

Conkling’s exposure to the elements of the storm reportedly contributed to his death at the age of 58 on April 18, 1888. In his honor, donors financed an eight-foot-tall, 1,200-pound bronze statue of the statesman, which was dedicated in 1893. The figure now stands atop a granite pedestal in the southeast corner of Madison Square Park at 23rd Street and Madison Avenue.

On nearby 22nd Street during the storm, Mayor Abram Hewitt governed New York City while hunkered down at his residence at 9 Lexington Avenue. Ironically, just weeks before the blizzard, Mayor Hewitt had introduced initial plans for a state-of-the-art underground transportation system. Shortly after the storm, he was “convinced now that the blizzard would have one good effect…as it shows the necessity for an underground rapid transit railroad and for getting the wires underground,” according to American Heritage.

The Mayor’s proposal, however, was originally viewed as a financial liability by operators of the elevated railways. “Owners of the elevateds opposed it, despite the overcrowding of their systems,” wrote Roger R. Roess and Gene Sansone in The Wheels That Drove New York: A History of the New York City Transit System. “The elevateds were making money on their crowded trains, and had no desire to dilute their investment by building additional lines.”

But after a decade of debate, the mass transit plan became policy when the first completed section of the New York City subway system made its debut at the City Hall station in Manhattan on October 27, 1904. Mayor Hewitt, who died of jaundice a year earlier on January 18, 1903 at the age of 80, later received the posthumous name acknowledgment of ‘Father of the Subway.’

The transit idea launched by Mayor Hewitt and the impact of the Great Blizzard of 1888 may have also given rise to the formation of “the modern American mayor,” as well as a citizenry seeking “greater protection,” noted The Atlantic on January 26, 2015. “In 1888, the Great White Hurricane bore down on the metropolises of the eastern seaboard, destroying infrastructure and paralyzing commerce. The devastation it left behind convinced voters that America’s burgeoning cities could function only if local governments assumed a larger, more proactive role.”

Header Credit: The New York Times

Thumbnail Credit: The Brooklyn Museum