Inventor Nikola Tesla Takes on Tech at Radio Wave Building

Jul 6, 2021

To commemorate the New York City designation of July 10, 1997 as Nikola Tesla Day, the Flatiron Partnership recalls the electric power inventor’s life in the neighborhood during the 1890s. Tesla resided and conducted scientific experiments at the Gerlach Hotel, now known in his honor as the Radio Wave Building at 49 West 27th Street, between Sixth Avenue and Broadway. Wireless remote control was one of Tesla’s notable creations, and he held its first demonstration at the 1898 Electrical Exhibition in Madison Square Garden on 26th Street.

Photo Credit: Commons WikiMedia

Born on July 10, 1856 in the Croatian village of Smiljan, Nikola Tesla was the fourth of five children. His father was a Serbian Orthodox priest, and mother, a household appliances inventor and manager of the family’s farm. While in high school, their son Nikola could “do integral calculus in his head,” notes thoughtco.com, and was so inspired by the demonstrations of electricity in his physics class that it “made him want to know more of this wonderful force.” He would receive a college scholarship for further study at Austria’s Graz Polytechnic School.

In 1882, Tesla accepted an offer to work at Thomas Edison’s Continental Edison Company in Paris. Two years later, he relocated to New York City for a job opportunity at Edison Machine Works, along “with the hope that Edison would help finance and develop a Tesla invention, an alternating-current (AC) motor and electrical system,” wrote The New York Times on December 30, 2017. “But Edison was instead investing in highly inefficient direct-current (DC) systems, and he had Tesla re-engineer a DC power plant on Pearl Street in Lower Manhattan.”

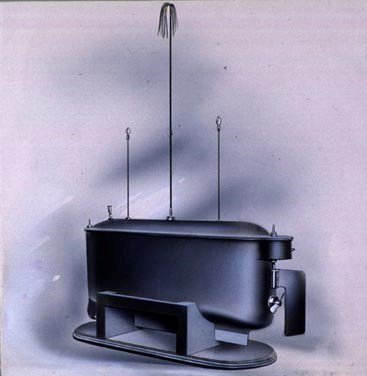

Pictured: The first practical remote-controlled robot via PBS

According to history.com, Tesla “worked there for a year, impressing Edison with his diligence and ingenuity. At one point Edison told Tesla he would pay $50,000 for an improved design for his DC dynamos. After months of experimentation, Tesla presented a solution and asked for the money. Edison demurred, saying, ‘Tesla, you don’t understand our American humor.’” Tesla left the Edison team, and the pair soon engaged in an electrical power rivalry known as the “War of the Currents.” Their competition included the 1892 bid by the Westinghouse Electric Corporation, where Tesla sold his AC patent and was now a consultant, and Edison’s General Electric firm vying for Chicago’s World’s Fair electricity contract, which Westinghouse won.

During 1892, Tesla had also moved to the Gerlach Hotel at 49 West 27th Street, between Sixth Avenue and Broadway. Constructed as French flats between 1882-83, the 11-story structure was designed by August Hatfield. But by the 1890s, it was operating as a hotel. Explained Richard Munson in Tesla: Inventor of the Modern about the tech pioneer’s time there, “After arising at 6:30 a.m., having gotten three hours of sleep, Tesla enjoyed a light breakfast, performed a few gymnastic exercises, and began his daily thirty block walk” pass Madison Square Garden and Madison Square Park to his Lower Manhattan lab. Tesla had installed at the Gerlach, a “receiver on the hotel’s roof in order to capture some of the first radio transmissions from his downtown workshop,” wrote Munson. The author also revealed that while Tesla strolled, he “counted his steps, making sure they were divisible by three.” His “obsession with the number three and fastidious washing,” notes history.com, were “dismissed as the eccentricities of genius.”

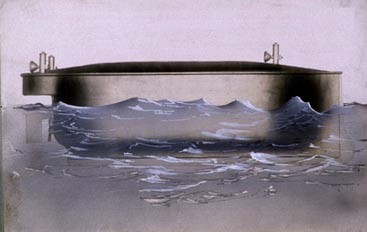

Pictured: Submergible version of Tesla’s remote-controlled craft.via PBS

By 1898, Tesla was ready to showcase one of his most innovative inventions, the first radio-controlled vessel, at an exhibit held in Madison Square Garden on 26th Street. The event’s opening day on May 2nd included a wired message from President William McKinley in Washington, D.C. The Commander in Chief expressed that it gave him “great pleasure to open the Electrical Exhibition in Greater New York, and to participate in this wonderful demonstration of the latest method of recording and publishing by means of electricity,” reported The New York Times on May 3, 1898. “I am glad to know that the resources of the wonderful electrical arts have already been so far advanced in the United States that American electrical goods are welcome the world over.”

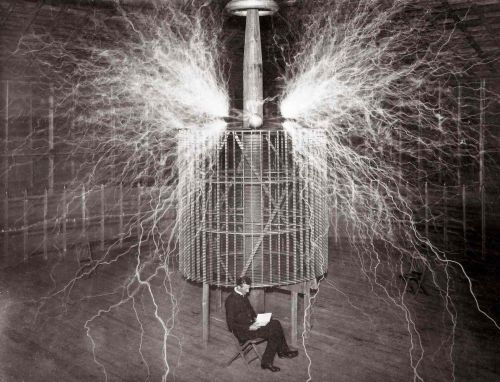

Photo Credit: Nikola Tesla demonstrates his Tesla coil “Magnifying Transmitter via ThoughtCo

Tesla’s presentation was considered to be “a scientific tour de force, a demonstration completely beyond the generally accepted limits of technology,” according to pbs.org. “Everyone expected surprises from Tesla, but few were prepared for the sight of a small, odd-looking, iron-hulled boat scooting across an indoor pond (specifically built for the display). In an era when only a handful of people knew about radio waves, some thought that Tesla was controlling the small ship with his mind. In actuality, he was sending signals to the mechanism using a small box with control levers on the side. Tesla’s device was literally the birth of robotics.”

This groundbreaking technology inside the Garden was not the only sign of change around the neighborhood. At the end of the 19th century, the Gerlach had also temporarily shut its doors in 1899, and Tesla made a move to Midtown Manhattan. “In his heyday,” wrote Time magazine on November 27, 1944, Tesla “lived at the Waldorf-Astoria and had a fabulous reputation as a host. He invariably took his guests to his laboratory and treated them to an electrical display, which included the then startling trick of passing 1,000,000 volts through his body.” Tesla continued to occupy hotels most of his life, which included a 10-year stay at The New Yorker Hotel, where he reportedly died of coronary thrombosis on January 7, 1943 at the age of 86.

Photo Credit: Radio Fidelity of Guglielmo Marconi

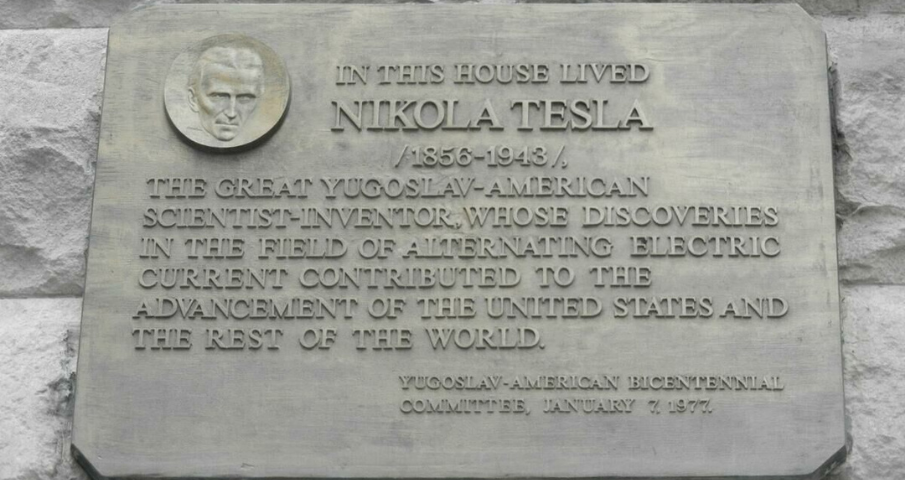

Six months after his death, the U.S. Supreme Court upheld an earlier decision on Tesla’s radio patent, thus naming him the real inventor of the radio, not Guglielmo Marconi, who had received the 1909 Nobel Prize in Physics for his work in wireless telegraphy. “The Court had a selfish reason for doing so,” notes pbs.org about the controversial ruling. “The Marconi Company was suing the United States government for use of its patents in World War I. The Court simply avoided the action by restoring the priority of Tesla’s patent over Marconi.” In recognition of Tesla’s triumphs in radio technology while living and working in Madison Square, a commemorative plaque was placed at 49 West 27th Street by the Yugoslav-American Bicentennial Committee on January 7, 1977, which was also 34 years after Tesla’s passing.

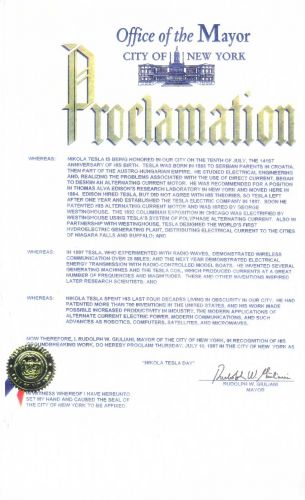

Pictured: Decree of Nikola Tesla mentioning his background, contributions to science, and to the general public via Tesla Society

Then, 20 years later, a proclamation to declare July 10, 1997 as Nikola Tesla Day was issued by New York City Mayor Rudolph Giuliani on the 141st anniversary of Tesla’s birth. The decree read, in part, “Nikola Tesla spent his last four decades living in obscurity in our city. He had patented more 700 inventions in the United States, and his work made possible increased productivity in industry, the modern applications of alternate current electric power, modern communications, and such advances as robotics, computers, satellites, and microwaves.”

Thumbnail: Department of Energy

Photo Credit: Atlas Obscura