David Glasgow Farragut, U.S. Navy’s First Admiral

May 19, 2021

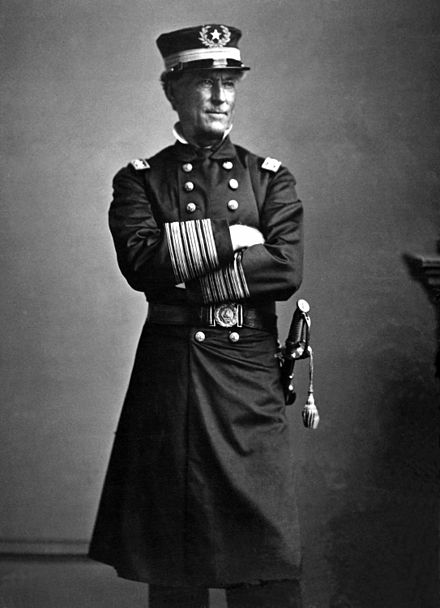

In observance of Memorial Day, the Flatiron Partnership remembers David Glasgow Farragut, the U.S. Navy’s first Admiral. This year marks the 140th anniversary of the military legend’s Memorial Day 1881 statue dedication in Madison Square Park. Farragut, a Tennessee native with Spanish and Scotch-Irish heritage, became a naval commander for the North during the American Civil War. He is best known for his victory against the South at Alabama’s Battle of Mobile Bay where he spoke his immortal words, “Damn the torpedoes, full speed ahead!”

Photo Credit: Wikipedia

Born in a cabin on July 5, 1801, near Knoxville, Tennessee, David (né James) Glasgow Farragut was the second son of George (né Jorge) Antonio Farragut-Mesquida, a Spanish merchant seaman turned farmer. George’s wife Elizabeth Shine hailed from North Carolina. A few years after the birth of David, the Farraguts and several of their children relocated to a 900-acre farm in New Orleans, Louisiana. In 1808, however, Elizabeth passed away from yellow fever.

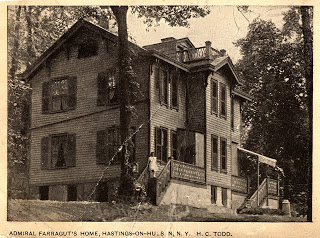

Photo Credit: Hasting Historical Society

Following the loss of his wife, George would often take the children sailing on nearby Lake Pontchartrain. In the book The Life of David Glasgow Farragut (written by his son Loyall), David recalls those childhood years, “When the weather was bad, we usually slept on the beach of one of the numerous islands of the Lake, or else on the shore of the mainland, wrapped in the boat sail, and, if the weather was cold, we generally half-buried ourselves in the dry sand.” But soon after his start as a single parent, George decided to place his children in the foster care of friends and relatives. David was adopted by family acquaintance Navy Captain David Porter, a move that launched the beginning of Farragut’s remarkable career spent at sea.

At the age of 9, Farragut was mentored by Porter to become a Midshipman. The pair would then serve on the Essex ship during the War of 1812. Subsequently, Farragut was promoted to Prize Master in charge of captured ships at the age of 12 and had excelled as a ship’s officer by the time he was 20. Following decades of naval leadership, Farragut would face his biggest military challenge in 1864. It was also during this period that the veteran and his family made the decision to relocate to the North. Although a Southerner by birth and resident of Virginia, Farragut had become a Union loyalist. When Virginia seceded from the Union in 1861, Farragut, with his second wife Virginia and son Loyall, headed to Hastings-on-Hudson in New York State.

Farragut soon returned to life at sea for his historic battle at Mobile Bay. The crew and their 18 ships set sail for the Alabama coastline to close the Confederacy’s last port. “Farragut’s fleet of wooden ships, along with four small ironclad monitors, began the attack on Mobile Bay early in the morning of August 5, 1864,” notes thelatinlibrary.com. “When the smoke of battle became so thick that he couldn’t see, Farragut climbed the rigging of the Hartford and lashed himself near the top of the mainsail to get a better view. It wasn’t long before the Tecumseh, one of the monitors leading the way, struck a torpedo and sank in a matter minutes.” Farragut declared, “Damn the torpedoes, full speed ahead!,” and told his seamen to pursue their blockade plans. The fleet was able to stay on course, seize the port, and capture the Confederate’s most powerful ironclad vessel known as the Tennessee, which held up a white flag in surrender to the Union.

The momentous victory by Farragut and his shipmates pushed the naval hero into the spotlight as one of the country’s preeminent combat icons. The conquest also led to Farragut’s appointment to the newly created role of the Navy’s first full Admiral in 1866. “The Battle of Mobile Bay lifted the morale of the North,” writes history.com about the 1864 Gulf of New Mexico conflict. The win also helped determine the person would become the next occupant of the White House in 1865. “The battle of the bay became the first in a series of Union victories that stretched to the fall presidential election, in which the incumbent, Abraham Lincoln, defeated Democratic challenger George McClellan, a former Union general,” notes the website.

Photo Credit: Daytonian in Manhattan

Farragut’s celebrated status sparked debate about the Admiral’s own presidential bid. In 1868, however, Farragut reportedly declined to run for office. “I hasten to assure you that I have never for one moment entertained the idea of political life,” he said, “even were I certain of receiving the election of the Presidency.” The Farraguts were now Manhattan residents in a brownstone at 113 East 36th Street, between Park Avenue South and Lexington Avenue. The reported $33,000 property had been purchased by the Admiral in 1865 with a monetary gift he had received from a committee of lending merchants. But on August 14, 1870, Farragut would die of heart disease at the age of 69. Upon his passing, there was a huge outpour of support, with a public funeral held on September 30th, and businesses, including the Stock Exchange, closed in observance.

Farragut was buried in Woodlawn Cemetery on Webster Avenue at East 233rd Street in the Bronx, now a National Historic Landmark and final resting place for many of the “Who’s Who of American History.” A decade later in Manhattan, the New York Farragut Association honored the military giant with a donated 9-foot bronze monument of Farragut to be installed in the northern section of Madison Square Park at 25th Street. Neighborhood sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens and area architect Stanford White, collaborators on the 26th Street Madison Square Garden, were the designers of the statue and its pedestal with extended exedra wings.

Photo Credit: Madison Square Park

The May 25, 1881 Farragut monument dedication ceremony in Madison Square Park was held “in the presence of a throng of distinguished spectators, and with an imposing military display,” reported The New York Times the following day. Hundreds of ticket holders, as well as dignitaries, were seated on benches and stools surrounding the vicinity of Madison Square Park. And, according to The Times, “the balconies of Delmonico’s and the Hotel Brunswick were filled with ladies and gentlemen, and all the windows and neighboring roofs were put to use.”

William H. Hunt, Secretary of the Navy, who was a keynote speaker at the event, said that the monument “stands a becoming ornament of this great and brilliant Metropolis,” wrote The Times. “In the midst of the haunts of busy men, intent on worldly and mere material pursuits, let it stand for all time to illustrate the nobler and higher aims of life; let its lesson be to all who shall pass beneath its shadow a lesson of patriotism purer than gold, more precious than the acquisitions of commerce!” Mayor William Grace, who had accepted the statue on behalf of the City of New York, noted, according to The Times, that “in one respect the venerable Admiral remained like the Midshipman of the Essex–his heart was always young. In manners and life he was always simple as a child–so plain and unostentatious that, at first meeting him, one was at a loss to reconcile his quiet and reserved presence with the idea of the heroic Farragut.”