An 1800s Skating Marathon Sparks Reform

Jan 6, 2022

January marks the launch of a new year and often the start of health and fitness resolutions. In recognition of this annual fitness ritual, the Flatiron Partnership recalls the popularity of the aerobic sport of roller skating in the late-1800s and how the hobby led to a safety protocol in the aftermath of a historic marathon at Madison Square Garden.

Original Madison Square Garden c. 1879 – Photo Credit: Wikipedia

In 1885, a pair of roller skates cost $6 and total sales had reportedly reached more than $20 million in America. “There are about 50,000 rinks in the country,” wrote the Saturday Evening Post on April 18, 1885, “and the demand for skates is greater than the supply.” According to americanheritage.com, “warehouses were converted to rinks, and men, women, and children flocked to them to glide ‘round and ‘round on the smooth wooden floors.” So-called ‘rinking,’ notes the website, was “such a popular Sunday pursuit that church attendance dropped off.”

Roller skating had evolved as “the principal pastime of citizens of every age and condition—business men went to work on skates, and skating parties were much in vogue among the fashionable,” wrote Herbert Asbury in All Around the Town. Even “several leading citizens and public officials seriously advocated equipping the police force with roller skates, contending that a patrolman could then easily overtake a criminal.” In addition, The New York Times on May 18, 1885 noted “elopements, betrayals, bigamous marriages, and other social transgressions were traced to the association of the innocent with the vicious upon the skating floor.”

Couple Rolling Skating in 1909 – Photo Credit: The Vintage News

The roller rage also caught the attention of amateur and elite athletes, as well as sports promoters. On February 22, 1885, it was reported that a six-day race would be held from March 2-8 in Madison Square Garden, then located on 26th Street and Madison Avenue. “Champion skaters signed up to compete, and the field also included some Pedestrians (ultrarunners),” writes ultrarunninghistory.com. “Frank Hart, 27, a celebrated Black champion brought his running endurance talents to the event. The winner would receive $500 and a diamond belt valued at $250.” A total of 36 men enrolled in the race.

During the marathon’s first evening, more than 11,000 spectators were in attendance to watch the skaters race, notes ultrarunninghistory.com. The website also described the crowd as “upscale” and “no smoking was allowed and the bar didn’t receive much business with stacks of kegs of beer untouched. Women stood five deep against the railing applauding the passing racers.” The skaters carried coffee pots, sucked on lemons and oranges, and drank ginger ale.

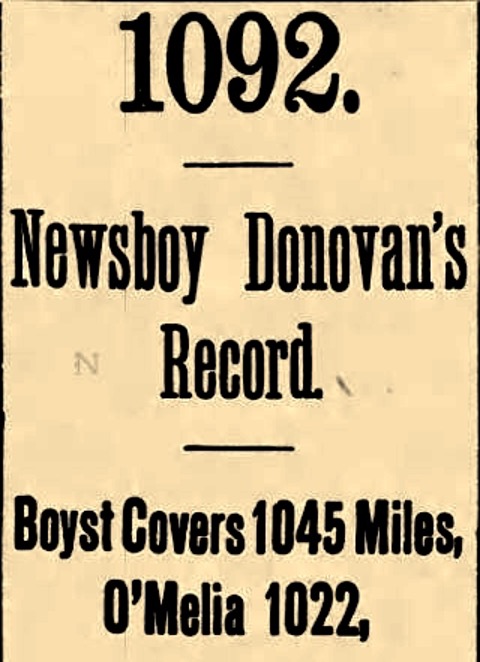

With the arrival of the race’s final day, the winner was declared. The titleholder was newsboy William Donovan, 18, from Elmira, New York and the son of Irish immigrants. Donovan had skated his way to victory upon completing 1,092 miles. In addition to the championship belt and monetary award, he also received a pair of gold-mounted skates. Following the race, however, Donovan’s feet “were in such a condition when he left the track that his stockings could not be removed,” notes ultrarunninghistory.com. Then, unexpectedly and just one month after his win, Donovan died of acute pericarditis on April 5th, reportedly caused by exposure after recovering from pneumonia he contracted due to being outdoors so soon after the marathon.

1885 News Clipping – Photo Credit: Ultra Running History

“Too much skating, as Donovan proved, was dangerous,” writes boweryboyshistory.com. Besides Donovan, another skater also purportedly died from an illness induced by the marathon. Joseph Cohen, 26, a dry goods clerk from Brooklyn, succumbed to acute cerebral meningitis on March 16th. Although a second marathon was booked for May, notes the website, this time “participants were handpicked, only the most experienced and healthy, including a few surviving the last go-round.” According to The New York Times on April 15, 1885, an inquest jury involved with the Cohen case recommended a law to offer a form of safety to skaters by prohibiting “owners and managers of rinks from allowing any match or exhibition which will keep the contestants on the floor of the rink any time exceeding four hours in duration.”

Header Photo Credit: Ultra Running History.

Thumbnail Photo Credit: Science Museum.